Criminal Mischief: Episode #43: Gunshot Wound Analysis

LISTEN: https://soundcloud.com/authorsontheair/43-gsw-analysis

PAST SHOWS: http://www.dplylemd.com/criminal-mischief.html

SHOW NOTES:

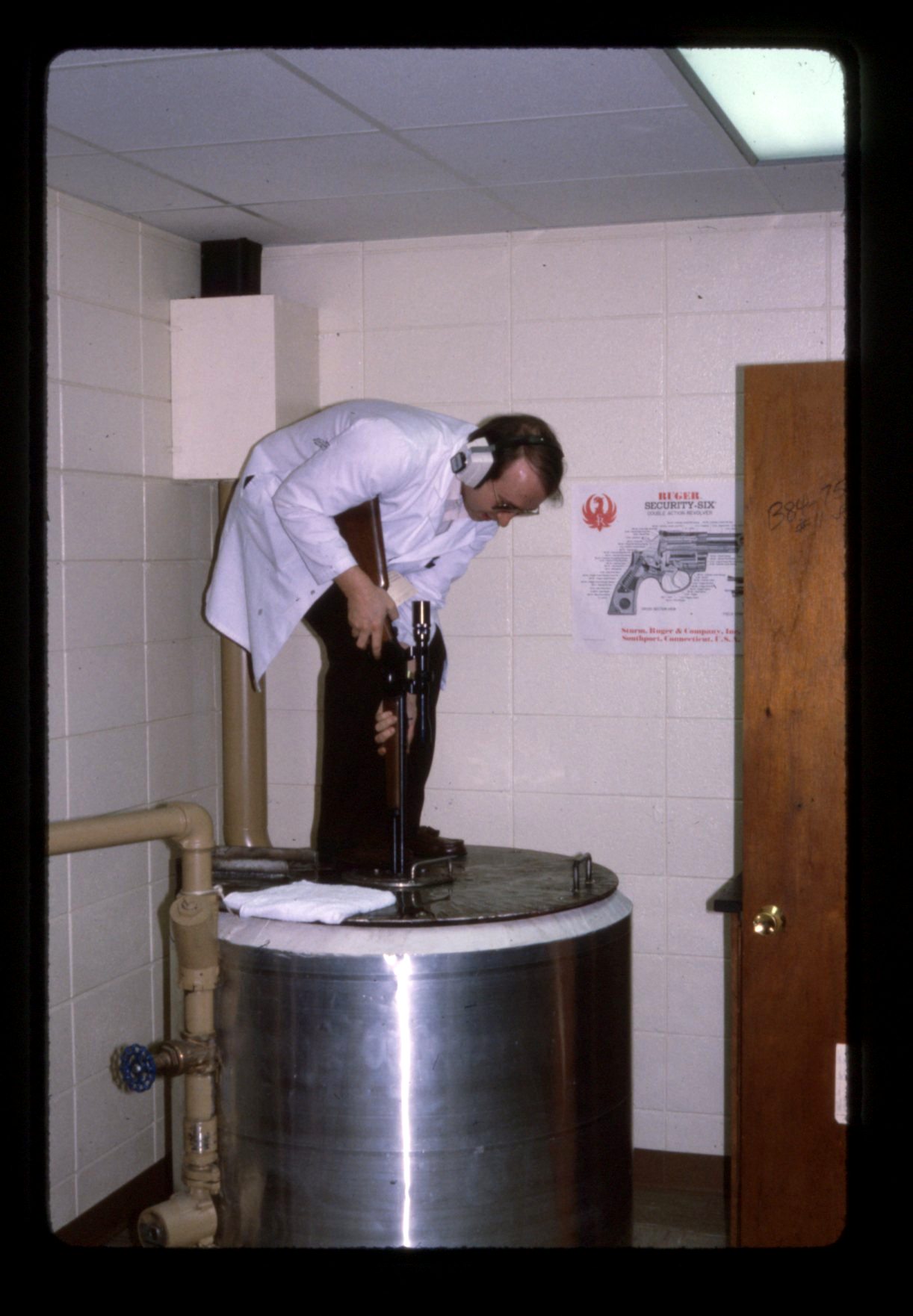

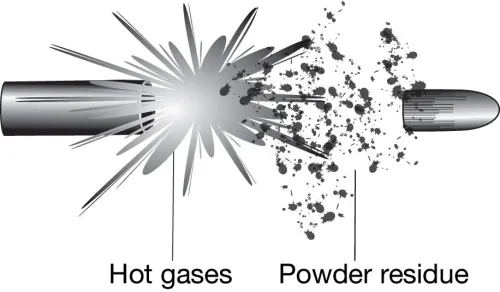

In the criminal investigation or injuries or deaths from gunshot wounds (GWSs), the anatomy of the entry and exit wounds, particularly the former, can reveal the nature of the weapon, the bullet size and characteristics, and of great importance, the distance between the muzzle and the entry wound. This distance can be a game changer when distinguishing between a self-inflicted wound (suicidal or accidental) and one from the hand of another (accidental or homicidal). It can also support or refute suspect and/or witness statements and help with crime scene reconstruction. A wound from a gun several feet away can mean something much different as opposed to one pressed tightly against the victim’s skin.

FROM FORENSICS FOR DUMMIES:

Studying Entry and Exit Wounds

Even when a bullet enters a body, leaving an entry wound, it does not necessarily come back out, or create an exit wound. More often than not, the bullet remains within the victim. When evaluating GSWs, an ME searches for and examines entry and exit wounds and tracks down any bullets retained within the victim. Although the distinction isn’t always apparent, the ME also attempts to distinguish between entry wounds and exit wounds because doing so can be critical in reconstructing a crime scene. Knowing the paths the bullets followed can implicate or exonerate suspects or help determine which bullet caused lethal injury.

The character of a wound produced by a gunshot depends upon several factors, including:

1—The distance between the victim and the muzzle of the gun

2—The caliber and velocity of the bullet

3—The angle at which the bullet enters the body (if it does)

4— Whether the bullet remains within the victim or passes completely through, exiting the body (a through‐and‐through gunshot wound)

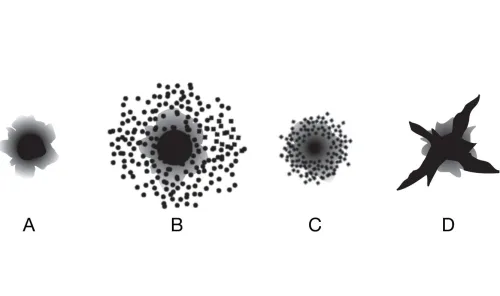

The anatomy of a gunshot entry wound depends upon the distance between the gun muzzle and the point of entry. Wounds may have an abrasion collar (a), tattooing (b), charring (c), or a stellate pattern (d).

The ME can estimate the distance from which a single bullet was fired by looking closely at the entry wound:

If the muzzle was 2 or more feet away from the victim, the entrance wound usually is a small hole, with an abrasion collar (a blue‐black bruising effect in a halo around the point of entry). Some black smudging can also occur where the skin literally wipes the bullet clean off the burned gunpowder, grime, and oil residue it picks up as it passes through the barrel of the gun (a).

If the muzzle was between 6 inches and 2 feet from the point of entry, the skin may appear tattooed or stippled. This effect is the result of tiny particles of gunpowder discharged from the muzzle embedded in the skin, in a speckled pattern around the wound (b).

If the muzzle was less than 6 inches from the victim, the gunshot produces a hole, a more compact area of stippling, a surrounding area of charring (from the hot gases expelled through the muzzle), and a bright red hue to the wounded tissues (c).

If the muzzle is pressed against the victim when the gun is fired, hot gases and particulate matter are driven directly into the skin, producing greater charring and ripping the skin in a star‐shaped or stellate pattern (d).

Exit wounds, on the other hand, typically are larger than entry wounds because the bullet lacerates (cuts or tears) the tissues as it forces its way out through the skin. The shape and size of an exit wound depend upon the size, speed, and shape of the bullet.

For example, soft lead bullets are easily deformed as they enter and pass through the body, particularly if they strike any bony structures along the way. When that happens, the bullet may become severely misshapen, which, in turn, produces more extensive tissue damage that often results in a gaping, irregular exit wound.

Distinguishing entry wounds from exit wounds is not always easy for the ME, particularly when the exit wound is shored, which means clothing or some other material supports the wound. The ragged nature of most exit wounds is caused by the bullet ripping its way through the skin. However, if the victim’s skin is supported by tight clothing or the victim is against a wall or other structure, the skin is less likely to tear. The exit wound therefore will be smaller and less ragged, and it will look more like an entry wound.

FORENSICS FOR DUMMIES Info: http://www.dplylemd.com/book-details/forensics-for-dummies.html

Howdunnit:Forensics Info: http://www.dplylemd.com/book-details/howdunnit-forensics.html